Windletter #122 - Ming Yang plans a 50 MW twin-rotor floating wind turbine

Also: why the blades of large wind turbines fail, hybridizing a combined cycle with 800 MW of wind power, the largest monopiles in history, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Reference provider of O&M services, engineering, supervision, and spare parts in the renewable energy market. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of specialized circular economy solutions and services for renewable energies. More information here.

🔹 Nabrawind. Design, development, manufacturing, and commercialization of advanced wind technologies. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

The most read in the latest edition: Woodmac’s report on the future of the wind market, the tattoo inspired by the motherf*ckin’ wind farms, and Ming Yang’s announcement of its plans to open a factory in the United Kingdom.

In addition, last Friday we published a feature in collaboration with RenerCycle, where we detailed the entire dismantling and material recovery process of the Muel wind farm. Check your inbox or read it below 👇

Now, let’s get to this week’s news. And you’ll have to forgive me for opening once again with Ming Yang as the main headline, but what they’ve just announced is simply out of this world.

Ming Yang plans a 50 MW twin-rotor floating wind turbine

China is once again pushing the boundaries of offshore wind. During the China Wind Power 2025 fair, held on 21 October in Beijing, Ming Yang Smart Energy, led by its founder and CEO Zhang Chuanwei, unveiled the development of a 50 MW floating wind turbine with a twin-rotor design, a concept that would double the capacity of the world’s largest turbines and set a new benchmark for the industry.

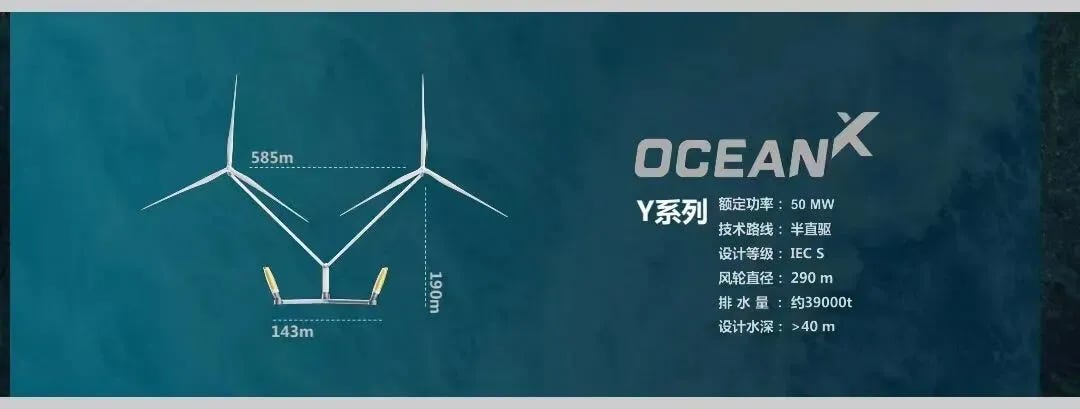

The 50 MW model consists of two 25 MW turbines (although for some reason, many sources mention 24.5 MW) with 290-metre rotors mounted on a V-shaped structure inspired by the architecture of OceanX, the 16.6 MW (2 × 8.3 MW MySE 8.3-180) floating prototype that Ming Yang deployed last year.

The leap from one model to the next is staggering, tripling the total power output.

As can be seen in the image shown during the fair, the turbines’ hub height would be 190 metres and the total width of the floating platform 143 metres. The image also mentions 585 metres of distance between nacelles, but that cannot be correct. This should refer to the total combined span of both rotors (290 + 290 + 5 metres of clearance between blade tips in the middle section).

For now, the project remains in a conceptual and theoretical phase, according to several media reports. It is expected that a real prototype could reach the water within two to three years.

The logistical challenges involved in assembling and transporting such a massive structure are by no means minor, nor are the port and crane requirements. One only has to recall the video of the 16.6 MW installation to grasp the scale.

Just ten units of this turbine would be enough to reach 500 MW of installed capacity, a clear indication of the magnitude of Mingyang’s ambition.

The question is whether this is truly the right path to reducing floating wind costs, versus other voices that advocate for smaller, more standardised, and industrialised designs.

In addition to the twin-rotor model, Mingyang also unveiled its new 25 MW single-rotor floating turbine with a 290-metre rotor, which will become the base model for its future floating range.

The presentation in Beijing comes right after Ming Yang announced a £1.7 billion investment to build a factory in Scotland, likely at Ardersier Port (Inverness).

It also follows only weeks after Goldwind installed the prototype of its own 16 MW floating turbine, currently the largest single-rotor turbine in the world.

🔧 Why do large wind turbine blades fail?

In recent times, several reports have surfaced about failures in large wind turbine blades. Although these incidents are relatively rare, such news tends to go viral, giving the public the impression that they occur more frequently than they actually do.

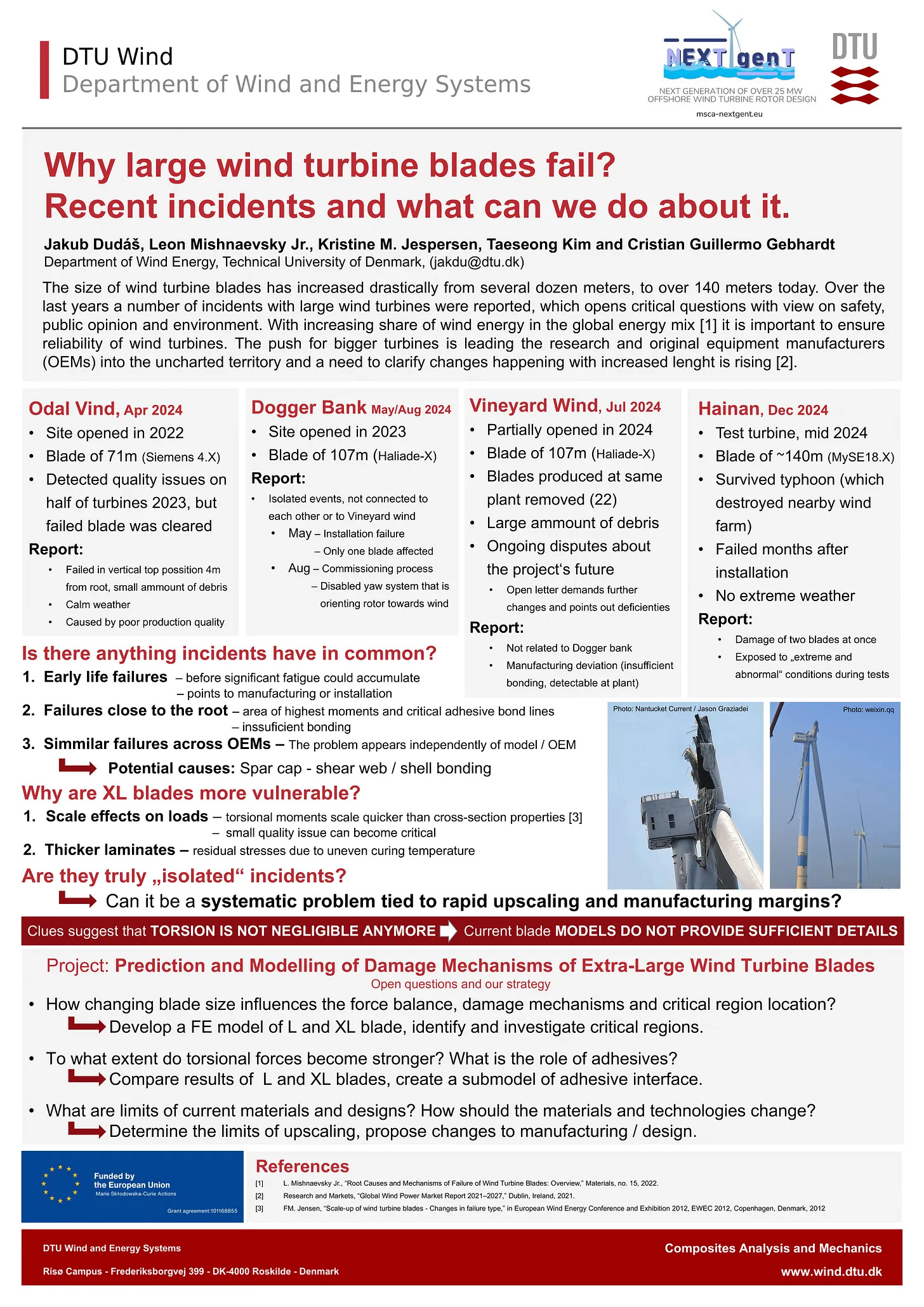

A group of researchers from DTU has developed a poster compiling some of the latest large-blade incidents, including Dogger Bank, Vineyard Wind, and Ming Yang’s prototype.

At Windletter, we even dedicated a main feature to the challenges OEMs face when dealing with blades of such enormous size.

In this context, a recent study by ORE Catapult in collaboration with RWE has sparked considerable discussion. Its findings suggest that turbine blades could extend their operational life significantly, in some cases by up to 50% beyond their original design life.

ORE Catapult engineers tested a blade from RWE’s fleet with 20 years of real operation, accelerating its ageing process in the laboratory at a rate equivalent to one year of real-life wear every 48 hours.

The tests, conducted at ORE Catapult’s facilities in Blyth, showed that with targeted adjustments and advanced monitoring techniques, it is possible to extend blade lifetime by up to an additional 50%.

This research also invites reflection on the evolution of blade design within the industry. One could argue that, in the early years, safety margins were generous, whereas today, with increasing turbine sizes and mounting cost pressure, designs have become more optimised and consequently more susceptible to failure.

🚢 An oil tanker nearly collides with an offshore turbine in the Netherlands

Recently, the vessel Eva Schulte, measuring 145 metres in length and carrying 21 crew members, was left adrift after an engine failure and came dangerously close to colliding with turbines at a wind farm operated by Swedish energy giant Vattenfall.

According to Martin ter Braak, Strategic Communication Advisor at Vattenfall, who shared the incident on LinkedIn, a “quick and brave response” from the Dutch Coast Guard and the Royal Netherlands Sea Rescue Institution (KNRM) prevented what could have been a serious accident.

WindEurope has reminded that EU countries are already implementing maritime spatial planning schemes to ensure safe navigation routes around wind farms, although some member states have not yet fully developed these plans, which are mandatory under European legislation.

📉 Hopes for floating wind fade as delays mount

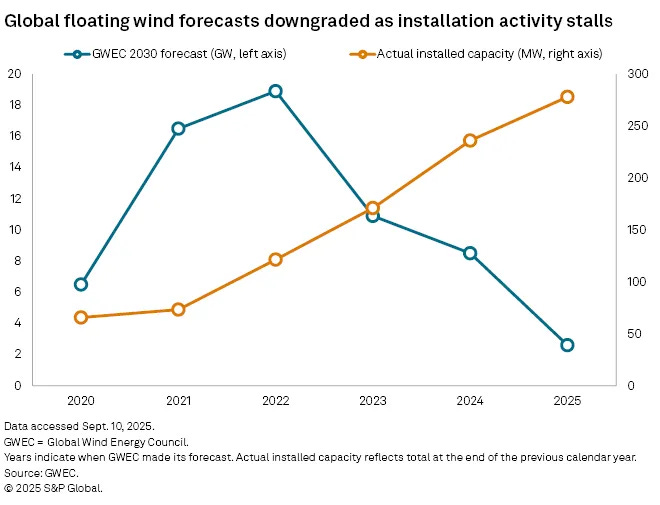

An interesting article from S&P Global takes some air out of the “hype” that had built up around the floating wind industry.

Over the past five years, high expectations and optimistic forecasts surrounded this technology, but a significant slowdown has now become evident.

The chart shared by S&P Global is particularly revealing. GWEC has drastically revised its forecasts in recent years: it now expects “only” 2.6 GW of installed capacity by 2030, compared with the 18.9 GW it projected just three years ago.

In reality, global installed floating wind capacity barely reaches 278 MW, representing only 0.3% of total offshore wind capacity, according to GWEC data.

We’ve already discussed some of the first large-scale floating wind farms expected to come online in future Windletter editions.

It’s definitely a topic worth exploring in greater depth… I’m adding it to my ever-growing notebook of ideas.

🗺️ How many MW fit into an offshore area?

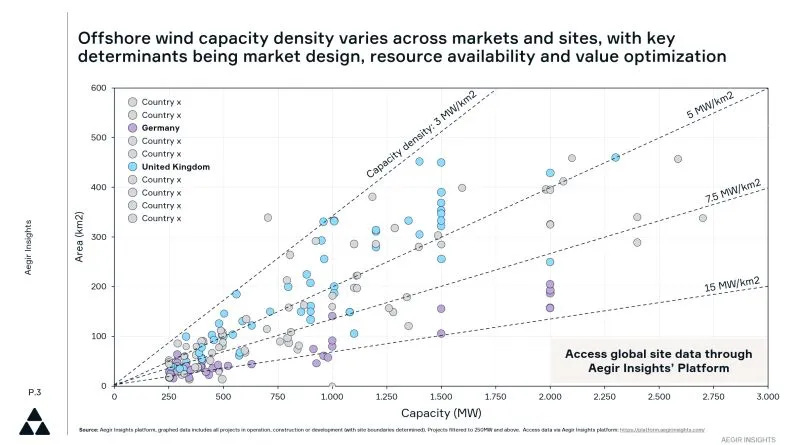

The team at Aegir Insights continues to share some of the most interesting charts on social media.

The latest shows the power density of different maritime areas across Europe. By power density, they refer to the number of megawatts per square kilometre (MW/km²) that can fit within a given offshore zone.

It is important to keep in mind that in many countries, maritime areas are auctioned and allocated first, with subsequent steps such as securing grid connection capacity coming later. Therefore, knowing how much capacity can optimally fit within your area is key.

When designing a layout, parameters such as potential exclusion zones, permitting constraints, available resource, and wake-effect optimization must all be considered.

The data show that power densities range from less than 3 MW/km² to more than 15 MW/km², a remarkably wide spread. The contrast between Germany, with very high densities, and the United Kingdom, with generally lower ones, is particularly striking.

For those interested in digging deeper into the topic, a couple of NREL papers and presentations are cited in the comments section (1 and 2).

⚡ Repsol to hybridize a combined-cycle plant with 805 MW of wind power

Repsol and Forestalia have announced a partnership to develop in Escatrón (Zaragoza) Spain’s largest hybridisation project, and possibly one of the largest in Europe, combining an 818 MW combined-cycle power plant with fifteen wind farms totaling 805 MW.

Grid access is currently one of the main bottlenecks for new renewable development in Spain. There is barely any capacity available at substations, much of it occupied by projects that may never be built but hold onto their permits until the very last day before expiration.

In this context, project hybridisation has become a solution for many developers, who can integrate new capacity using an already existing grid connection point. So far, the most common approach has been hybridising wind projects with solar, but more innovative combinations are now emerging.

Such is the case for Repsol and Forestalia in Escatrón, where wind and gas will share a grid connection point, optimising infrastructure and maximising the use of existing capacity.

The wind farms, still under development, already have a favourable Environmental Impact Declaration, and Forestalia will continue leading their development until commissioning.

The project will also be complemented by a nearby data centre being developed by a third party, which already has 402 MW of renewable self-consumption authorised by Red Eléctrica de España, along with more than 800 MW of backup capacity from this hybridisation. The combination will make the complex one of the most powerful in the country.

I must admit I’m really curious to see how the control system for this hybridisation will be designed, and how the variability of wind will be managed alongside the dispatchability of gas.

💨 Vattenfall plans a 2.9 GW onshore wind farm in Sweden

Vattenfall has submitted an application to the Land and Environmental Court in Umeå to develop the 2.9 GW Storlandet onshore wind farm in Gällivare municipality, northern Sweden.

According to several sources, the project could include up to 316 wind turbines reaching 295 metres in height. That figure doesn’t quite align with the 2.9 GW total capacity, as it would imply turbines of around 9.2 MW each.

It is also reported that the wind farm could generate around 9 TWh of electricity annually, equivalent to more than 3,000 full-load hours, an excellent resource for an onshore site. The energy produced would be primarily destined for the mining and steel industries, both key sectors in northern Sweden.

If the permit is approved, a process that could take up to three years, Storlandet would become the largest onshore wind farm in Europe, on a scale comparable to offshore projects and even exceeding some of them.

⚠️ Maersk cancels installation vessel 98.8% completed

A surprising piece of news comes from the US offshore wind sector, which continues to face setbacks.

Maersk Offshore Wind has cancelled the construction of a wind turbine installation vessel that was 98.9% complete, built by the Seatrium Energy shipyard (formerly Sembcorp Marine) in Singapore.

The vessel, valued at about USD 475 million, was originally intended for Equinor’s Empire Wind 1 project.

It is hard to understand how a contract of this magnitude can be cancelled when the vessel is practically finished. While the specific contractual structure is unknown, logic suggests that Maersk must already have paid a substantial portion of the total amount.

According to Rivieramm, Maersk claims delays and construction issues, while Seatrium disputes the validity of the termination and is considering legal action for possible “wrongful termination.”

Several sources indicate that Equinor could purchase or directly charter the vessel from the shipyard or alternatively use other operators with available capacity.

As you may know, Empire Wind 1, located off the coast of New York and consisting of 54 × Vestas V236-15.0 MW turbines, faced a temporary construction halt under the Trump administration. Although work has since resumed without major delays, the pause caused significant cost overruns for the project.

🏗️ The world’s longest and heaviest XXL monopiles

During spring and summer, CS Wind Offshore successfully completed the production of several XXL monopiles reaching lengths of up to 123.6 metres and a record weight of 2,515 tonnes, marking a new milestone in offshore wind manufacturing.

The work was carried out at the company’s Lindø facility in Denmark. According to CS Wind, the fabrication process achieved an exceptionally low welding defect rate of just 0.05%.

In recent years, there has been much discussion about the depth limits for fixed-bottom offshore wind, with around 80 metres traditionally considered the upper threshold. However, we now see that this barrier has been surpassed by a considerable margin.

Of course, these monopiles will be considerably more expensive, but at least they are technically and economically viable if they have indeed been manufactured. And very likely a more economical and proven solution than floating wind in any case.

CS Wind Offshore has not disclosed (or perhaps could not disclose) who the client is or which wind farm these record-breaking monopiles will be installed in.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace, RenerCycle and Nabrawind our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.