Windstory #21- Renewables and the rural environment: two realities that can go hand in hand

The proactive attitude of some developers, good communication and well-understood social responsibility can make the difference.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

Windstory is the articles section of Windletter, where we publish single-topic analyses and share interesting stories from the wind energy sector.

From time to time, without a set schedule, a new edition of Windstory will arrive in your inbox.

Last week I had the opportunity to attend, invited by Endesa (part of Enel Group), the presentation of the second season of Conexión a Tierra.

Conexión a Tierra is a video podcast (sorry, presented in Spanish) whose aim is to get closer to the field and show, through real cases, how the rollout of renewable projects is being experienced in rural areas.

This kind of collaboration always sparks my curiosity, because beyond the general discourse, they allow us to learn about specific experiences and to ask questions that often remain outside the usual focus of the sector.

Listening directly to those involved in these projects, such as local residents, developers or local institutions, helps to better understand the challenges, expectations and also the opportunities that arise with the integration of renewables in rural environments.

And, as often happens, all this led me to keep pulling the thread and to dig a little deeper into the subject. So, I am sharing here some of the ideas and reflections that arose from the event.

🌱 Renewables and the rural environment: two realities that can go hand in hand

When a renewable energy developer arrives in a rural area with a new project, it is not uncommon for the first reaction to be one of a certain distrust or even rejection.

Fifteen or twenty years ago, when these projects were still a novelty, many were processed without much public repercussion. Partly because the level of information was lower and citizens did not always know very well what these facilities implied.

But the context has changed. Nowadays, there is practically no municipality where doubts, concerns or even opposition do not arise. And in many cases, it is understandable. Legitimate fears emerge: of the unknown, of a possible change in the landscape, of the tranquility or way of life of the place being altered.

That attitude of “better not to touch anything” often stems from a desire to preserve what is valued in the rural environment. Understanding that starting point is key for any dialogue process to work.

We live in a society that is more polarised than a few decades ago, where it is often difficult to find nuances. People feel more comfortable in firm positions, in black or white, although reality usually lies on a scale of greys.

Perhaps that is why, in recent years, we have seen how the strategies of many developers have evolved. And it is a positive change.

It is increasingly common for them to approach municipalities with a proactive and open attitude, not only in the final phases of development but from earlier stages. And not only with mayors or authorities, but also with neighbourhood associations, farmers, livestock breeders, businesses, sports clubs or any other relevant actors in the life of the town.

It is also becoming common to organise public presentations in the municipalities themselves to explain the details of the project, answer questions and speak openly about its impact. And, of course, to share what benefits it can generate for the local community.

That exercise in transparency not only improves the relationship with the territory but also helps counter some of the simplified (and often inaccurate) messages that circulate on social media or in the press.

It is normal for these projects to generate doubts. Some are completely understandable, and others are ideas that do not always match reality. Explaining things clearly, and doing so from the outset, helps make the debate fairer for everyone.

🌾 Renewables and agriculture do not compete for land

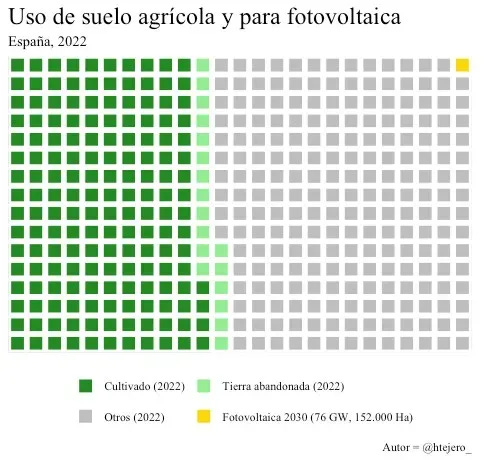

One of the arguments most often repeated in public debate is the supposed competition between renewables and agriculture for land use. It is often claimed that solar farms are displacing crops and livestock, with consequences such as the loss of food sovereignty or rising prices. A concern that should be put into context.

The data show a very different picture. According to a study by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, only 0.2% of the utilised agricultural area in Spain, about 47,300 hectares, is currently occupied by photovoltaic installations.

In addition, between 2012 and 2022, 82% of the new hectares destined for solar farms came from dryland areas with lower agricultural productivity. Only 11% were irrigated land, and 7% were forest or non-agricultural surfaces. This is no coincidence: developers usually opt for less productive land from an agricultural point of view, which also tends to be more affordable.

Even projecting strong growth in photovoltaics, the use of agricultural land would remain very limited. The National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC) sets an ambitious target: reaching 57 GW of ground-mounted photovoltaic capacity by 2030. A goal that will not be easy to achieve.

That would mean occupying approximately 114,000 hectares of solar panels (assuming 2 ha/MW), which is equivalent to just ~0.5% of the ~24 million hectares of agricultural land. In other words: more than 99.5% of agricultural land would still be available for its traditional uses.

Even so, this does not diminish the importance of carefully planning where projects are installed and how they interact with existing rural activities.

🦅 Renewables and biodiversity. Environmental impact yes, but also opportunities for regeneration

Environmental impact is, without a doubt, one of the most sensitive aspects when it comes to implementing renewable projects. It is not about idealising the facilities: all forms of electricity generation have some kind of environmental impact on the territory.

But precisely for that reason, the key lies in choosing technologies with lower impact and, above all, in applying measures that help reduce it to a minimum.

In Spain, all projects must undergo an Environmental Impact Assessment (DIA) approved by the competent authority. This procedure ensures that the possible effects on biodiversity have been evaluated and that measures have been established to mitigate them. Complying with the DIA means complying with the law.

But more and more developers are choosing to go further, applying additional measures that not only reduce the impact but also generate direct environmental benefits in the area.

Because these projects, in addition to generating energy, can also provide resources that were not previously present in the area. And if used well, they can help preserve and improve the environment.

For example, at the Puerta Palmas solar plant in Extremadura, more than 10 hectares are dedicated to the conservation of the little bustard, making it the first steppe bird reserve within a solar plant.

⚖️ Renewables also bring resources and create jobs

Renewable energies can not only coexist with other economic activities: in many cases, they can complement them.

During the event we learned about the case of some livestock farmers who graze their sheep inside a photovoltaic plant. What is known as “solar grazing”. The flock thus gains access to good quality pasture, free of pesticides, while helping to keep the land clean naturally. A clear example of mutual benefit.

Speaking with the shepherd, he told us that at first he was sceptical, but that this agreement has made his daily life much easier. Before, he had to travel long distances in search of grazing areas, whereas now he has quality pasture assured close to home. The milk from those sheep is then used to produce what they have named “solar cheese.”

Another interesting example is the apiaries installed by Endesa in several of its photovoltaic plants, where the well-known “solar honey” is produced. A honey that, by the way, I have once again missed out on tasting… once more because I couldn’t take it in my hand luggage ☹️.

Of course, not all cases are the same. But when projects are designed with a local vision, they can generate additional income and new opportunities for those who live in the area.

💰 Leases and tax revenue

In addition to possible compatibility with other economic activities, renewable projects can generate direct economic returns for the territory, both through land rental and via taxation.

In the case of rentals, when they are private, the income usually remains with families in the municipality itself. And if the land is municipal, the rent directly increases the resources of the town council. In both cases, rental prices are usually above market value and, often, also well above the agricultural profitability of the land.

On the other hand, there is the question of taxes, an issue about which there is still quite a lot of lack of knowledge. The truth is that a renewable plant can mean considerable income for municipal coffers, especially during the construction phase. In small municipalities, these amounts can make a real difference in their investment capacity and provision of services.

One of the most relevant taxes is the ICIO (Tax on Constructions, Installations and Works), popularly known as the “construction tax.” It can reach up to 4% of the project’s total budget.

If we are talking about investments of around €600,000/MW in the case of solar and €1,200,000/MW in the case of wind, a 50 MW wind farm can generate between €1.2 and €2.4 million in ICIO for the town council. That said, it is a tax that is paid only once, at the beginning of the project.

On top of that are recurring taxes, such as the IBI (Property Tax) and the IEA (Business Activity Tax), which each year provide additional income for municipalities throughout the entire lifetime of the installation.

How that income is used is the responsibility of the competent administrations. In any case, one thing is to collect… and quite another is for that money to be translated into real improvements for the territory 🙂.

✒️ Conclusions

I could go on delving into many of these topics. Another question is whether they really have permission to invest it. But that would be a subject for another chapter. In fact, some, such as the real fiscal impact of renewable plants on municipalities and public finances, deserve a more detailed analysis, which I will save for another time.

But it is also true that something is changing. New ways of planning projects, engaging with the environment, and explaining what is intended are starting to appear. And there is also more awareness that this is not only about producing energy, but about trying, as far as possible, to bring real value to the territory.

The proactive attitude of some developers, good communication and well-understood social responsibility can make the difference.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.