Windletter #127 – The United States halts 5 offshore wind farms under construction: what’s going on?

What is the optimal size for offshore turbines, 99.8% of migratory birds avoid wind turbines, Vestas commissions the first V236-15.0 MW at sea, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Reference provider of O&M services, engineering, supervision, and spare parts in the renewable energy market. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of specialized circular economy solutions and services for renewable energies. More information here.

🔹 Nabrawind. Design, development, manufacturing, and commercialization of advanced wind technologies. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

Most read in the previous edition: the post with images of the modular blade, Portugal’s largest wind farm, and the low-noise monopile installation tech Osonic.

Erratum: in the last edition, we mentioned that the potential 500 MW deal Siemens Gamesa is negotiating in Egypt would involve the SG5.0-132 (2.0). However, that turbine is currently not even listed on their website. SGRE did sell the SG5.0-132 for a time, but following the suspension of the 4.X sales, the only available model is the SG5.0-145 (2.0), which is likely the one being negotiated for this 500 MW deal.

Now, let’s jump into this week’s news.

📢 United States halts offshore wind citing security concerns

On December 22, 2025, the Trump administration announced the immediate suspension of all offshore wind power projects under construction in the United States. The reason given is the risks to national security.

Background. Since early 2015, the Trump administration has targeted offshore wind. First it imposed a moratorium on new offshore concessions, then it tried to halt projects already underway:

In April 2025, it suspended construction activities at Empire Wind 1 (New York), although the order was lifted a month later following negotiations.

In August, it ordered the pause of Revolution Wind (Rhode Island/Connecticut), but a federal judge overturned the blockade due to lack of justification.

These precedents foreshadowed the major December halt, which simultaneously affects five projects.

Why is the government halting offshore wind? The official justification is to protect national security. According to the Pentagon, the massive offshore wind turbines interfere with coastal defense radars.

This argument has already been used to block the development of 13 wind farms in Sweden, as reported in Windletter. However, other countries like Poland see offshore wind as a defence opportunity. Projects like Baltic Power, in Polish waters and located less than 200 km from Kaliningrad (Russia), will equip their turbines with radars and sensors following national defence guidelines.

What’s more, each of the halted wind farms was assessed and approved by the Department of Defense during permitting, with no objections at the time. Some sources also point out that, as a mitigation measure, more modern radars and filtering algorithms exist to reduce the “noise” generated by turbines.

So many see “national security” as an excuse by an administration opposed to wind energy.

Affected projects and approximate construction status:

Vineyard Wind 1 – 806 MW (Massachusetts). Owners: Avangrid/Iberdrola and CIP. Turbines: 62 × 13 MW GE Haliade-X 220m. Status: ~90% complete (55 of 62 turbines installed)

Revolution Wind – 704 MW (Rhode Island/Conn.). Owners: Ørsted and GIP. Turbines: 65 × Siemens Gamesa SG 11.0-200 DD. Status: ~87% complete (58 of 65 turbines installed)

Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (Virginia) – 2.6 GW. Owner: Dominion Energy. Turbines: 176 × Siemens Gamesa SG 14.0-222 DD MW. Status: ~66% complete

Sunrise Wind – 924 MW (New York). Owner: Ørsted. Turbines: 84 × Siemens Gamesa SG 11.0-200 DD. Status: in 2025 the installation of monopiles and substation was completed

Empire Wind 1 – 810 MW (New York). Owners: Equinor and BP. Turbines: 54 × 15 MW Vestas V236-15 MW. Status: >60% complete

In total, 6 GW of wind power halted, raising alarm bells across the industry.

As you can imagine, the economic impact on developers is considerable. For example, Dominion Energy estimates it loses 5 million dollars for each day its wind farm remains halted. No small amount.

Some developers have already responded with legal action, including Dominion, Equinor and Ørsted, who have filed lawsuits in federal courts claiming the order is illegal and arbitrary, and requesting precautionary measures to resume construction. As mentioned, Revolution Wind previously succeeded in getting a judge to lift the suspension.

Next steps. According to the Department of the Interior, the pause will allow the study of mitigation measures for radar risks. The industry expects that after this review, or more likely through judicial intervention, construction will be allowed to resume in the short term. Though it remains to be seen at what cost.

🌪️ What is the optimal size for offshore turbines?

A PhD thesis tackles the million-dollar question in the offshore wind sector: what is the ideal size for offshore wind turbines? does scaling the technology further still add real value?

The study starts from the idea that optimisation can’t be done at the individual turbine level alone, but must be approached at the wind farm level, incorporating costs, production, wake effects, O&M, and revenue structure. This is not always easy, since the turbine designer and the infrastructure designer are usually different companies.

Moreover, the traditional goal of minimising LCoE now coexists with merchant scenarios, where each kWh has a different value depending on the time of day.

Some interesting conclusions from the thesis:

The optimal turbine size depends less on installed capacity and more on specific power (power–rotor ratio).

To minimise LCoE, the optimum is around 15–16 MW with ~230 m rotors, under North Sea assumptions. So we’re basically there already.

Changing wind assumptions or park density shifts the optimum, but without major LCoE improvements.

The study suggests that the marginal gains from further scaling are limited, reinforcing a growing belief in the industry: standardisation may be more profitable than continued growth.

You can read the full thesis here, and it’s also worth checking out the comment section on this LinkedIn post.

🦅 A german study suggests that 99.8% of migratory birds avoid wind turbines

The impact on birdlife—especially migratory species—is one of the most recurrent debates around wind energy and one of the most critical topics during environmental impact assessments.

Now, a study by the German Offshore Wind Energy Association (BWO) concludes that 99.8% of migratory birds actively avoid wind turbines, reducing the collision risk to much lower levels than previously assumed.

The analysis was carried out over a year and a half at a nearshore wind farm off the northern coast of Germany, tracking over four million flight paths—both daytime and nighttime.

Some key findings from the study:

The study challenges the traditional assumption that more bird migration leads to more collisions. No clear positive correlation is observed between migratory traffic rate (MTR) and collision risk.

Rotor-plane crossing rates were extremely low when turbines were in operation:

at night, one crossing every 132 hours on average with spinning rotors

with stopped turbines, crossings were 20 times more frequent, indicating less evasive behaviour

Avoidance rates were extremely high: 99.87% at night and 99.86% during the day for birds approaching rotor height with turbines in operation.

Preventive turbine shutdowns during migration peaks—based on the idea that more migration equals more collisions—are likely ineffective.

The study was conducted by BioConsult SH and funded by several offshore developers and operators, including Ørsted, RWE, Iberdrola, EnBW, and Vattenfall.

The study is available online at this link.

🌊 Vestas commissions the first offshore v236-15.0 mw

Vestas has reached a new milestone in offshore wind with the commissioning of the first V236-15.0 MW at sea, as part of the He Dreiht project developed by EnBW in Germany, in the North Sea.

This is the third operational unit of the model, the first fully commercial offshore one, after Vestas previously installed two onshore prototypes: the first in Østerild, at Denmark’s national wind turbine test centre, and the second at the port of Thyborøn, an interesting participatory project also in Denmark.

In parallel, the V236-15.0 MW is also being deployed in Poland, specifically in the Baltic Power project, developed by Orlen and Northland Power. With 76 turbines and 1,140 MW, Baltic Power will be Poland’s first offshore wind farm.

These are key moments for Vestas’ offshore business and its strong bet on the V236-15.0 MW, which has already secured over 11 GW of firm orders and preferred supplier agreements since its launch.

🏗️ BW Ideol invests in the floating project Méditerranée Grand Large

An interesting move by BW Ideol, which has become a shareholder in the Méditerranée Grand Large project, awarded in the French AO6 auction and developed by EDF Power Solutions and Maple Power.

The project, known as EMGL (AO6), will be located 25 km off the coast and will feature around 250 MW of floating capacity. It will be one of the first large-scale commercial floating wind farms in the French Mediterranean.

EDF and Maple Power had an agreement with BW Ideol since 2022, but now the technologist’s role is no longer that of a client-supplier, but of an industrial and technological partner with a 15% stake, reinforcing the project’s bankability and maturity at a critical stage. So it seems obvious that the floating platform will be BW Ideol’s design.

The participation is made through BW Ideol Projects Company (BW IPC), its development vehicle shared with the state-owned ADEME Investissement, which has up to €80 million committed for project development.

It appears to be a smart strategy by BW Ideol. On the one hand, entering as a partner gives them skin in the game, and on the other, it ensures their technology is used in a large-scale project, a crucial step for long-term success.

🌬️ Onshore wind in the West and China: diverging costs, converging strategies

An interesting article by Endri Lico from Wood Mackenzie discusses how the onshore wind sector has reached a turning point in 2025.

According to Lico—and as we’ve mentioned several times in Windletter—costs are following very different paths in the West and in China, but OEM strategies are becoming increasingly similar. Volume is becoming secondary, as manufacturers focus more on profitability.

A key data point mentioned by Lico is that turbine prices in Europe and the United States have increased by around 45% since 2020, reaching around $1–1.2 million/MW (€0.9–1.1 million/MW). This cost has remained steady despite the recovery in the prices of many materials and logistics.

This would indicate a clear decision by Western OEMs: to recover margins rather than grow in volume. WoodMac points out that 2025 may mark the cost peak, with some relief expected from 2027.

In China, the dynamic is different. After years of aggressive reductions, costs are beginning to stabilise. However, outside of China, Chinese OEMs continue to offer turbines at very low prices, around $400,000/MW (~€370,000/MW), leveraging scale and technology.

According to Wood Mackenzie, this value- and profit-oriented strategic shift has clearly boosted investor confidence. In 2025, the shares of major wind OEMs, both Western and Chinese, have risen by an average of 72% so far this year, as shown in the graph they published.

📉 Marginal capacity factor: more turbines isn’t always better

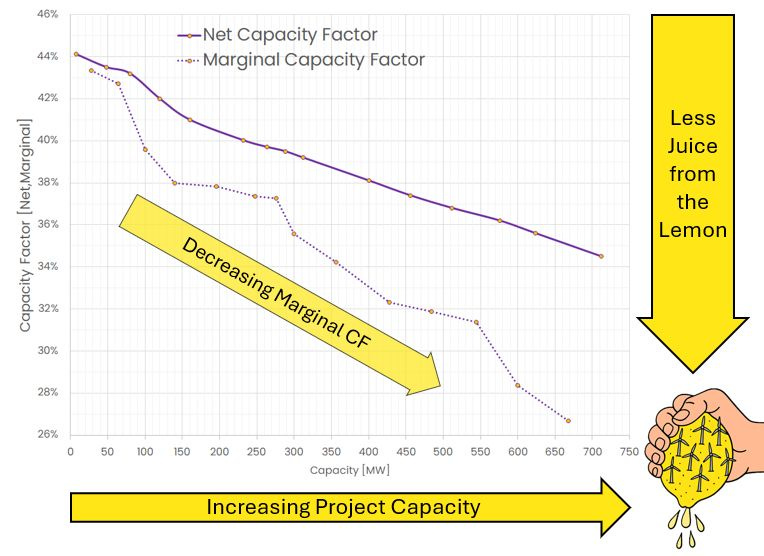

An interesting reflection shared by Jerry Randall from Wind Pioneers explores a rarely used yet valuable concept in wind farm design: the marginal capacity factor.

The idea is simple. The first wind turbine you place on a site goes in the spot with the best wind resource, free of wake losses, and therefore with the highest capacity factor. The second turbine is not as good. As you keep adding turbines, they’re installed in areas with less wind and wake losses between turbines also increase.

The result: the average capacity factor of the wind farm decreases as installed capacity grows.

That’s where the key concept comes in. The marginal capacity factor measures the performance of the next MW or turbine you add—not the average across the project.

If we look at the example shared by Randall:

The wind farm starts with a capacity factor of 44% (one single turbine).

As installed capacity increases, both the marginal capacity factor of each additional turbine and the total average capacity factor drop.

At 600 MW, additional turbines only yield a 28% marginal CF.

At a certain point, depending on the project, the question stops being technical and becomes purely economic: does each additional turbine improve the project’s profitability?

🛠️ Ingenuity to overcome obstacles: unloading blades in Martinique

Stunning images have surfaced from the island of Martinique, located in the Lesser Antilles and an overseas department of France.

The photos reveal an extraordinary logistics operation: unloading turbine blades directly from the sea and lifting them over a cliff.

The solution is remarkable. A barge positions itself near the shoreline and transfers the blade to a temporary jetty. From there, a large crane installed atop the cliff hoists the blade from sea level up to the island.

This kind of tailor-made setup is used in locations where conventional logistics simply won’t work. In this case, Martinique’s main port may not have the necessary capabilities, or it may be physically impossible to transport blades from the port to the wind farm site due to narrow roads or tight turning radii.

So, an unorthodox but highly effective alternative was chosen. It’s a vivid reminder of the logistical complexity in the wind sector. No doubt many were sweating through this manoeuvre…

See the rest of the images in this LinkedIn post by Delvis Da Silva Andrade.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace, RenerCycle and Nabrawind our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.