Windletter #98 - Manufacturing extra-long blades might be more complicated than it seems

Also: Denmark's offshore auction left deserted, aftermarket fire suppression systems, Siemens Gamesa sells Gamesa Electric, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you enjoy the newsletter and are not subscribed, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Specialized services in operation and maintenance, engineering, supervision, inspection, technical assistance, and distribution of spare parts in the wind sector. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of solutions and specialized services in the circular economy for renewable energies, including comprehensive dismantling of wind farms and waste management, refurbishment and sale of components and wind turbines, management and recycling of blades and others. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

We start the year 2025 full of energy and with a very interesting edition.

The most-read stories from the latest news edition were: the documentary video of the first GE 3.6 MW-154m, bringing wind energy to Namibia, and the CEO of Blue Float visiting Mingyang.

And now, let’s dive into this week’s news.

🛠️ Manufacturing extra-long blades might be more complicated than it seems

The technological race to design and manufacture ever-larger wind turbines has undoubtedly been one of the key focuses of the wind industry in recent years.

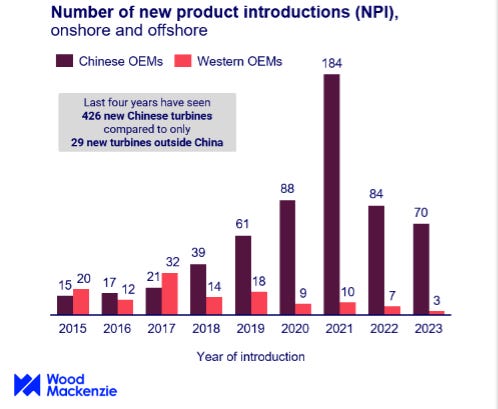

Western OEMs have slowed down (but not halted) this race in pursuit of profitability and improvements in the quality and reliability of their products. Vestas has even publicly commented on this matter.

However, Chinese manufacturers are more active than ever, becoming the new leaders of this race and far surpassing the sizes of Western turbines. So far, there’s no sign of deceleration on their horizon.

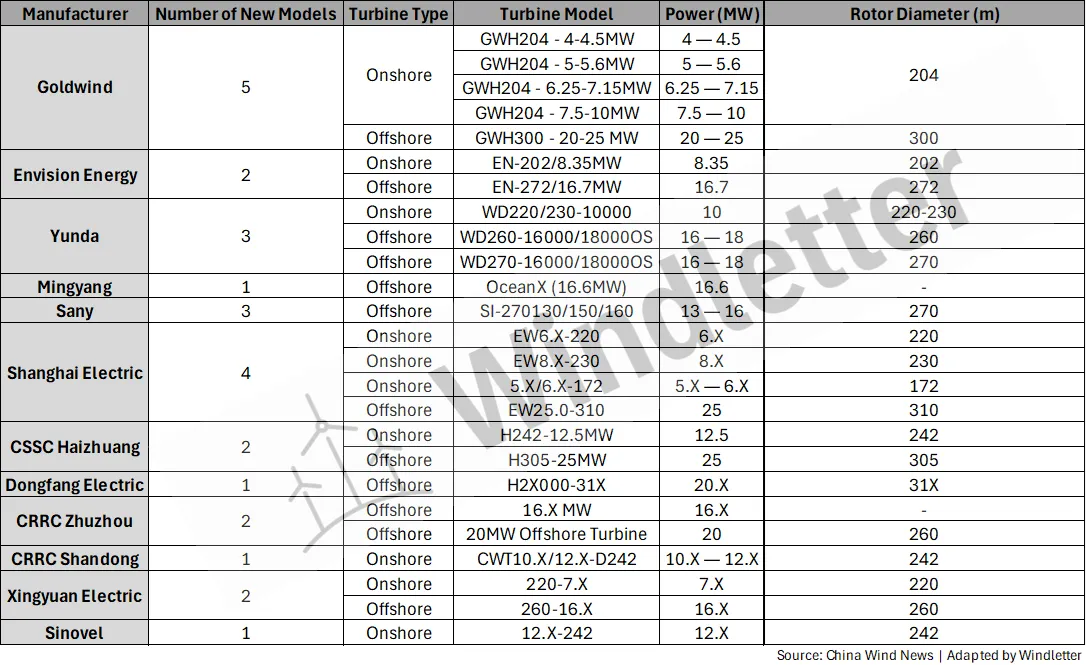

Just take a look at the list of new models presented at the China Wind Power 2024 exhibition to get an idea of the sizes we’re talking about (pay attention to the rotor diameter column).

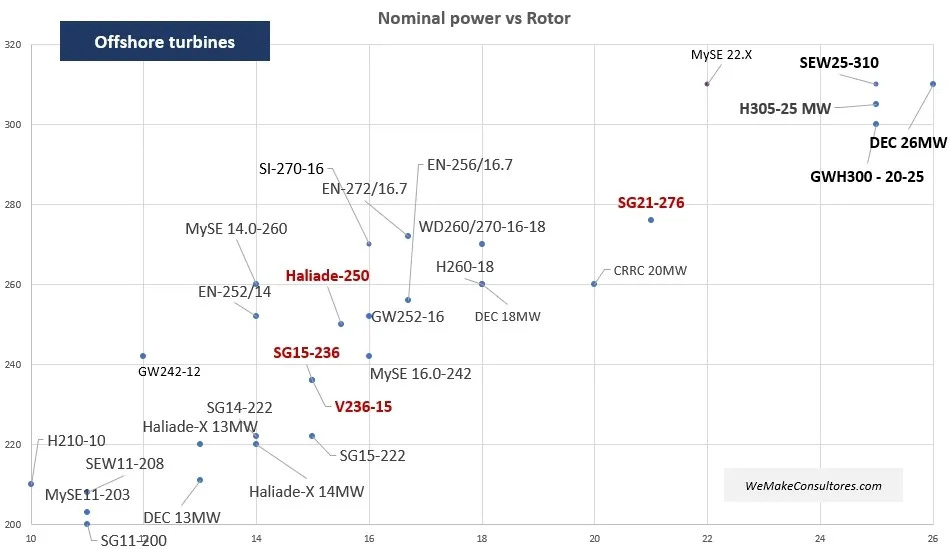

To understand this phenomenon more visually, the following chart from our friend Kiko Maza is revealing, with the largest Western OEM models sitting in the middle of the table (and even then, the Haliade 250 doesn’t seem likely to hit the market anytime soon).

As you can see, the only Western turbine that closely follows the giants presented by Chinese OEMs is Siemens Gamesa’s SG21.0-276 DD (commercial name unconfirmed). This model hasn’t even officially entered the market, and SGRE has made no public statements about it. You can find all public information about this model here:

This rapid growth in turbine size brings many, many challenges. For instance, Western OEMs have faced several setbacks with their new-generation turbines. Siemens Gamesa’s well-known issues with their 4.X and 5.X models, GE Vernova’s struggles with the Haliade X, and Vestas’ blade problems are just a few examples.

Many of us wondered whether Chinese OEMs could withstand this accelerated growth without encountering similar problems to their Western counterparts. Spoiler: judging by recent news, it seems they cannot.

A few weeks ago, the breakage of two blades from the world’s largest operating wind turbine, Mingyang’s MySE18.X-20MW prototype with a 292-meter rotor, went viral across the press and social media. This occurred just months after its commissioning.

The news was so widespread that Mingyang had to issue an official statement on LinkedIn, explaining the incident and citing "extreme and abnormal conditions during testing, which caused the blades to exceed their design load limits."

But Mingyang is not the only manufacturer facing blade issues. According to Chinese press reports, Sany’s onshore 15 MW prototype with a 270-meter rotor diameter also experienced a blade failure.

And it doesn’t stop there. The same article notes that Sany’s blade failure marks the fifth instance of a blade breaking on a Chinese turbine of over 15 MW since October this year, covering both test benches and operational prototypes. Worth mentioning, to say the least. Although it is also true that it’s better for it to happen in the prototypes.

And what are the reasons behind all these failures?

Honestly, I don’t know the exact causes, nor am I an expert in the subject. However, speculating a bit, one plausible reason could be that Chinese OEMs have started using carbon fiber in their blades to adapt to increasingly large rotors. Previously, according to reputable international consultancy data we’ve accessed, Chinese OEM blades were primarily made with fiberglass.

Fiberglass has a lower strength-to-weight ratio compared to carbon fiber. This means that for very large rotors, the blades must be bulkier and heavier. Consequently, this requires building a larger and more robust nacelle and tower, significantly increasing costs.

Perhaps this material shift has been a critical factor in these problems. But this is just speculation.

Surely some blade expert is reading this, so if you can think of any other reason, I’m all ears 🙂.

🛑 Denmark's offshore wind auction left deserted. What happened?

This topic has garnered significant attention over the past few weeks, but I believe it’s worth discussing here.

In April, Denmark launched a 3 GW offshore wind auction with several unique characteristics:

Negative bidding: The Danish government, following Germany’s example, introduced the concept of negative bidding, where developers must pay a concession fee to the government during the 30-year lease period.

No revenue guarantees: The auction did not offer a long-term tariff or a CfD (Contract for Difference) to provide revenue stability and visibility, leaving developers to bear 100% of the market risk.

Mandatory state participation: The auction required the Danish government to hold a 20% equity stake in the projects. While common in Denmark’s gas sector, this was a first for wind.

As a result, the auction ended without a single bid. There’s no investor appetite under these conditions. Additionally, Denmark’s small economy makes it challenging to secure long-term PPA clients who can provide revenue visibility.

Is it catastrophic that the auction failed? Not really. Reckless bidding would have been worse. This is likely a strong signal to redesign the auction criteria.

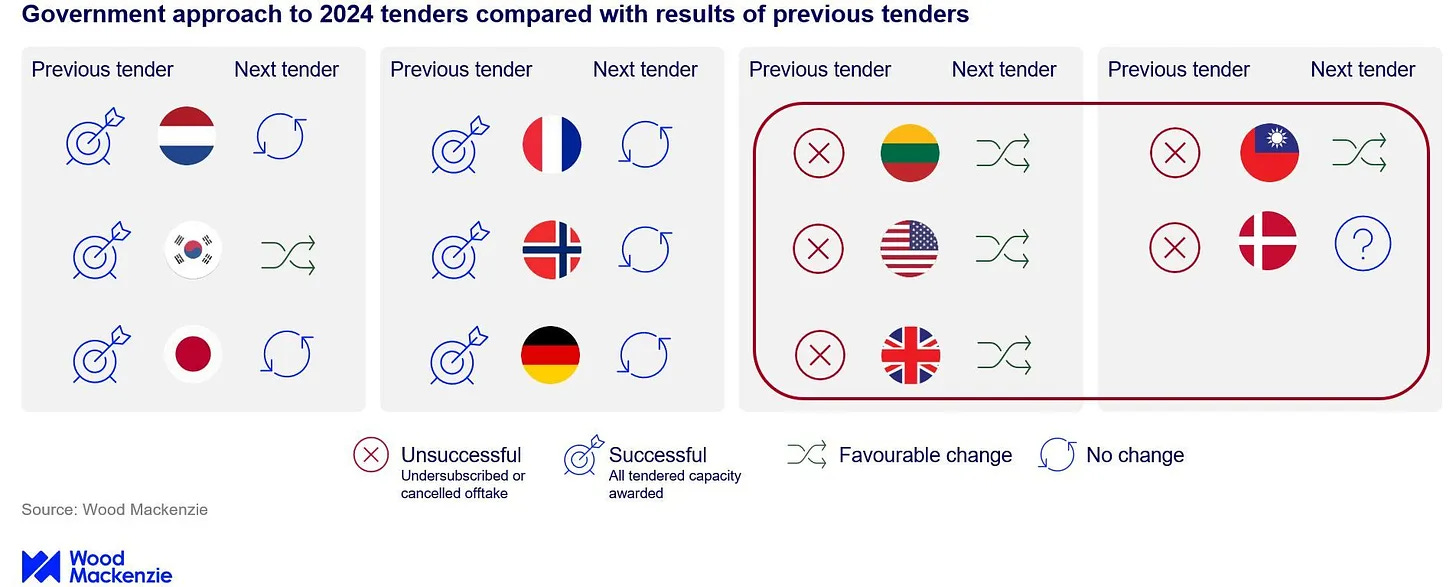

Wood Mackenzie shared an infographic illustrating how governments respond to auction outcomes, suggesting that Denmark may adjust the criteria and relaunch the auction in a few months.

♻️ RenerCycle closes 2024 with several milestones achieved

Our sponsor RenerCycle, specializing in industrial and technological solutions to drive the circular economy in renewable energy, concludes the year with a recap of its 2024 milestones:

🏢 Opening of its headquarters in Pamplona.

🏭 Commissioning of a logistics and metal materials recovery center.

📃 The Government of Navarra declared RenerCycle and Waste2Fiber's project a regional investment of interest.

🧪 Launch of industrial R&D projects aiming for #ZeroWaste in wind energy.

♻️ Over 100 tons of blades processed during tests for recycling technology development.

⚙️ Initial refurbishment and resale projects of components for second-life use as spare parts.

📢 Contributions to national and international forums on circular economy in renewables.

RenerCycle, which began operations in 2022, is currently developing its technological and operational capabilities.

Follow their LinkedIn account for updates.

🔧 Testing and validation centers: a strategic resource for the wind sector

The technological race toward larger wind turbines also requires testing and validation centers adapted to their size. These centers are used to validate new designs and ensure their reliability over the expected 20-30 years of service life.

Kiko Maza reviews the main testing centers worldwide and their evolution, focusing on Chinese manufacturers and suppliers.

The case of Sany is particularly surprising, along with all the graphic material they share on their YouTube channel.

🔥 Aftermarket fire suppression systems in wind turbines

Fires in wind turbines are a very delicate issue, both due to the catastrophic consequences they can cause and the reputational risk faced by wind farm owners.

For this reason, it is becoming increasingly common to equip wind turbines with fire suppression systems that actively respond to any potential fire outbreak in the nacelle. In fact, some countries and regions even require these systems to be installed by law.

Nowadays, it is usual and recommended to install these systems from the outset, as an optional feature requested from manufacturers during the purchasing process. However, for older machines, aftermarket systems are available and can be installed on turbines already in operation.

This is precisely what I found on the LinkedIn profile of Iñigo López Zubiri, Head of O&M Wind Technical Services at Enel Green Power. In collaboration with the company E Fire USA, Enel has installed fire suppression systems on the 72 Gamesa 2 MW turbines at the Oaxaca wind farm.

The system consists of small box-shaped devices installed in areas prone to fires, such as the inside of electrical cabinets or locations where sparks might occur. Upon detecting smoke, the systems release a gas that extinguishes the fire.

🏭 Siemens Gamesa sells part of Gamesa Electric to ABB

The rumor that Siemens Gamesa was considering selling its electrical components manufacturing division, Gamesa Electric, had been circulating for some time. Finally, it has been confirmed that the buyer is the multinational ABB, a possibility already rumored in August last year.

Ultimately, Siemens Gamesa has not sold Gamesa Electric in its entirety. The transaction with ABB is limited to the power converters, inverters, and control cabinets business for the wind, solar, and energy storage industries. The generators and electric motors business is not included.

The sale, subject to regulatory approvals and customary closing conditions, is expected to be completed in the second half of 2025. Additionally, as part of the agreement, ABB and Siemens Gamesa have signed a long-term collaboration agreement.

For Gamesa Electric (now part of ABB), this opens up a window of opportunities to sell its wind products to other OEMs, something it previously couldn't do while under the SGRE umbrella. Interestingly, Juan Barandiaran, Managing Director of Gamesa Electric, who is also joining ABB, responded to Jose Luis Blanco, CEO of Nordex Acciona, with a direct comment: "new opportunities to collaborate?"

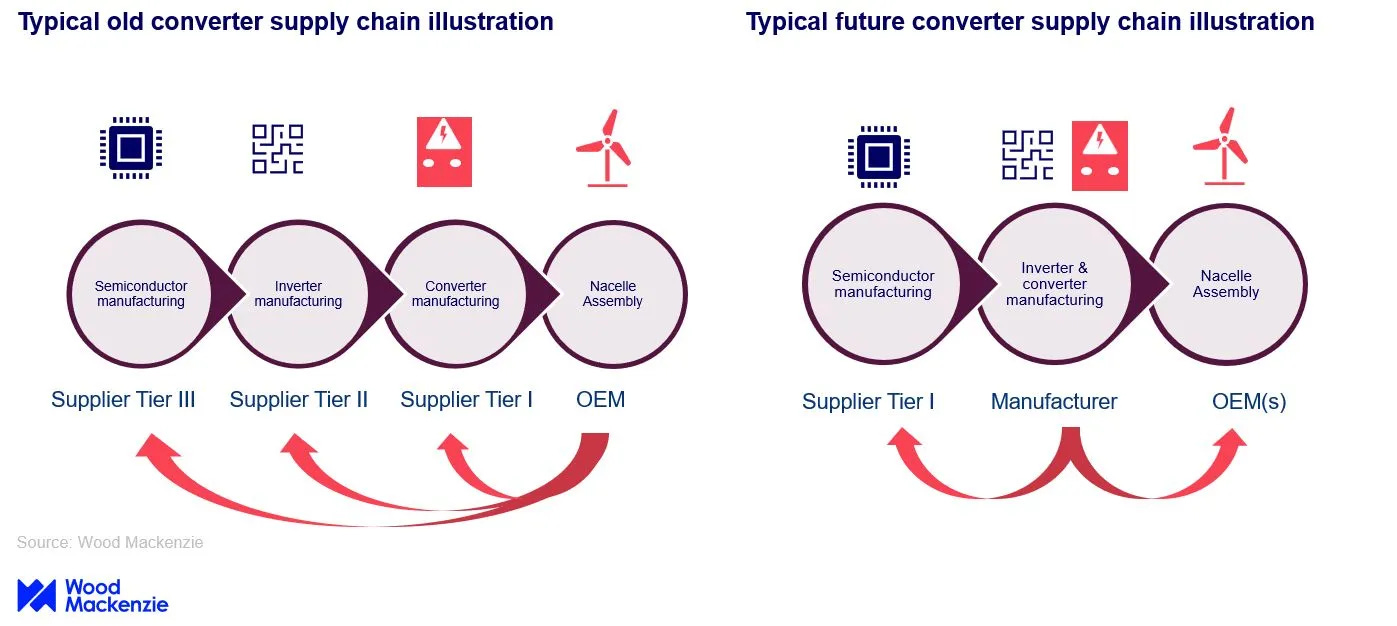

This sale is a move very similar to the one Vestas made almost two years ago when it sold three factories for converters and control cabinets to KK Wind Solutions.

The trend in the sector continues for OEMs to have less in-house manufacturing (known in the industry as "make") and more outsourcing (known as "buy").

On this topic, I appreciated the reflection and infographic shared by Endri Lico from Wood Mackenzie, which illustrates how one stage in the converter supply chain is being reduced:

💨 Goldwind manufactures the first nacelle of its 22 MW wind turbine

According to Recharge News, Goldwind has manufactured the first nacelle of its 22 MW model at its manufacturing plant in Shantou, a coastal city in China's Guangdong province.

It is reported that this wind turbine has a rotor diameter of 300 meters with 147-meter blades, and its first unit will be installed in the first quarter of 2025 at a yet-to-be-confirmed wind farm.

The announcement from Goldwind coincides with the public unveiling of the SG21.0-276 DD (unconfirmed name) by Siemens Gamesa, clearly indicating that the race for larger rotors continues.

Let’s recall that Goldwind installed the GWH252-16 MW in June 2023, a prototype with a 252-meter rotor diameter and 16 MW capacity, which at the time was one of the largest in the world.

🌄 Repowering, in one image

I really liked the following image shared by Statkraft’s LinkedIn account. It showcases the repowering project for the Montes del Cierzo I and II wind farms in Navarra.

Located in the municipalities of Tudela and Cintruénigo, these wind farms currently have an installed capacity of about 60 megawatts (MW) and consist of 84 Ecotecnia 44 wind turbines, each with a capacity of 600 kW. After the repowering, the number of wind turbines will be reduced to 15, representing a 77% reduction.

I think this is a great exercise in communication. Moreover, this wind farm is ideal for such a demonstration, as the turbines could be placed in a line, making the visual impact reduction from the repowering more than evident.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace and RenerCycle, our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.