Windletter #125 - The world’s cheapest wind power

Also: evolution of wind turbine size, first orders for the SG7.0-170, Paulo Soares leaves Sany Europe, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Reference provider of O&M services, engineering, supervision, and spare parts in the renewable energy market. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of specialized circular economy solutions and services for renewable energies. More information here.

🔹 Nabrawind. Design, development, manufacturing, and commercialization of advanced wind technologies. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

Sorry for the delay since the last news edition, but I can already tell you that I have a few semi-finished Windstory features that I think you’re really going to enjoy.

Last week we also published a feature where we tried to understand the reasons behind the strategic shift of major power companies towards investment in grids.

The most read from the last edition were: the article with data on the future of offshore in the UK, the post about modular blades, and the article on floater designs.

So, now yes, let’s go with this week’s news.

🌍 The world’s cheapest wind power

A few weeks ago, a piece of news made headlines across the industry: Saudi Arabia awarded 3 GW of onshore wind capacity with prices below €20/MWh, placing them among the cheapest projects ever seen worldwide (or at least, outside of China).

Specifically, the awarded PPAs offer a 25-year contract at a price of US$18.66/MWh (≈€17.5/MWh) for the 1,000 MW Shaqra project, and US$20.57/MWh (≈€19.3/MWh) for the 2,000 MW Starah project. At first glance, these figures defy almost any known benchmark in Europe or the US.

In the same tender, 12 GW of solar PV was also awarded at prices below US$14/MWh. Spectacular.

The developers of the wind farms are a consortium of ACWA Power (35.1%), PIF (34.9%), and SAPCO (30%). The projects are expected to reach commercial operation in Q4 2027 and Q1 2028 respectively.

According to official publications, the selected turbines are the Goldwind GWH204-10 MW (300 units in total), installed on 148-metre hybrid towers.

According to industry sources consulted by Windletter, this turbine supply contract may be between 50% and 70% cheaper than Western OEMs. In its earnings report, Goldwind reported a price of around €250k/MW for contracts awarded in China, which is absolutely rock bottom.

For comparison, European OEMs report an average selling price (ASP) to the market of between €700k and €900k/MW, three to four times higher than what this Saudi contract implies.

As is often the case with Chinese OEMs, the scope of the contract must be understood: the EPC contractor is also Chinese, Energy China (CEEC), and it is likely that these companies are absorbing a significant share of the costs typically included in the OEM supply: logistics, installation, local manufacturing of hybrid towers, domestic transport, etc. But the truth is that this remains unclear, or at least, we have not been able to confirm it.

Even so, it is hard to grasp how such a low price is possible, and not everything can be attributed simply to “the competitiveness of the Chinese supply chain,” since a Western OEM, even manufacturing 100% of its components in China, cannot come anywhere near a selling price of €250k/MW.

Industry sources suggest that this could be a strategic price set by China to push Western competition out of the Middle East market through aggressive pricing. What is clear is that, at these price levels, Western OEMs have likely assumed this market is lost.

It would be very interesting to know what real margin remains for Chinese manufacturers at these prices.

Precedents in Saudi Arabia

There is already a precedent in Saudi Arabia involving a Western turbine that can serve as a reference: the Dumat Al-Jandal project (400 MW), developed by EDF Renewables and Masdar, and equipped with 99 Vestas V150-4.2 MW turbines.

Commissioned in 2021, it was the country’s first wind farm and at the time also signed a record-breaking PPA at just ~US$21.3/MWh, this time with Vestas turbines. However, it is also true that this contract was awarded prior to the OEM crisis, when Western turbine prices were at their lowest point ever.

But… how is it possible to sign PPAs this cheap in Saudi Arabia? Several other factors help significantly, beyond securing a very low turbine price:

Reasonably high capacity factor: Saudi Arabia has regions with 35–45% capacity factor, especially along the northwest and central corridors.

Extremely low cost of capital: projects are financed through 25-year contracts signed with SPPC (Saudi Power Procurement Company), the state-owned offtaker. In practice, this implies near-sovereign risk, substantially lowering financing costs.

Massive scale and BoP/O&M optimization: very large projects (up to 3 GW in the latest awards) enable economies of scale. Additionally, being located in desert areas results in very low BoP costs.

Virtually nonexistent land and permitting costs: most land is state-owned, with no significant urban conflicts and far less complex environmental development than in Europe.

All in all, a very interesting project to follow closely. We may be looking at the largest onshore turbines ever installed outside China, as well as the largest onshore contract in history.

🏗️ Wind turbine size evolution by market and manufacturer origin

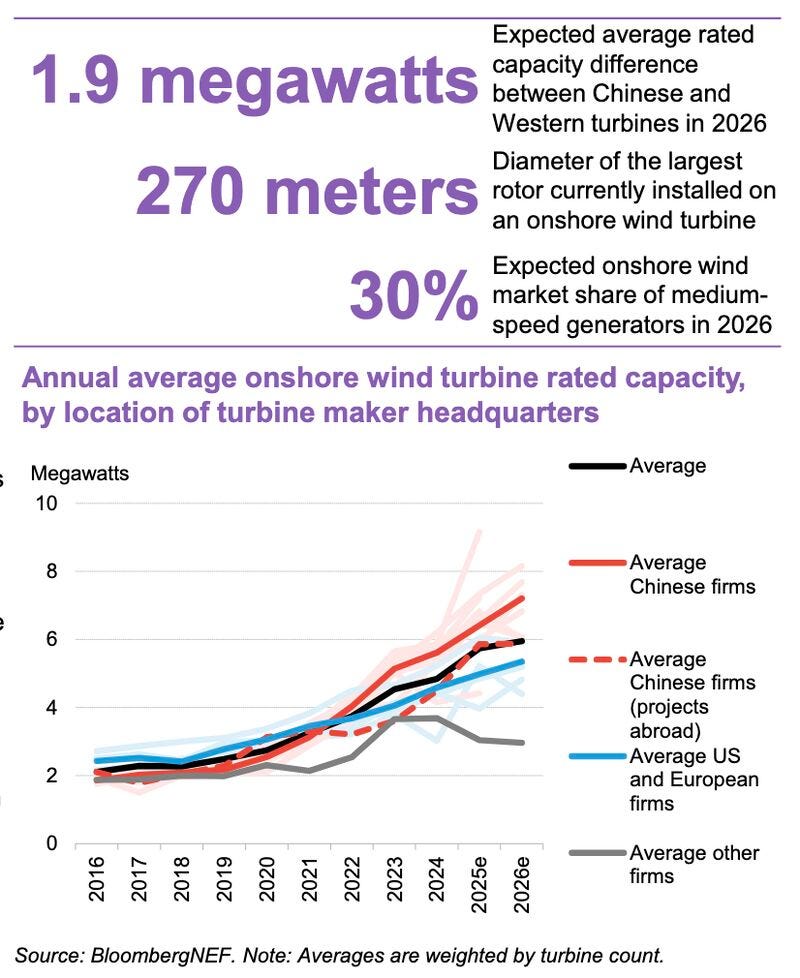

An interesting chart shared by Hou Sang (Samson) Cheng, Wind Supply Chain Researcher at BloombergNEF, illustrates how wind turbine size and rated capacity have evolved over time, based on two key variables:

Installation market: China vs the rest of the world

Manufacturer origin: Chinese, Western or other

The analysis is part of their latest Wind Turbine Technology Trends 2025 report, covering data from more than 16,600 wind farms installed globally between 2016 and 2026. Some highlights:

The average rated power of Chinese turbines reached 5.6 MW in 2024, compared to 4.6 MW in Western markets.

By 2026, the average capacity of onshore turbines manufactured by Chinese OEMs will exceed that of Western ones by more than 1.9 MW.

China’s curve began to surge in 2021, when average turbine sizes were still comparable between China and the West.

China now operates the world’s largest onshore rotor at 270 m diameter, a leap enabled by fewer logistical constraints and inland sites with moderate winds that benefit from longer blades.

BloombergNEF also estimates that medium-speed permanent magnet synchronous generators (MS-PMSGs) will reach a 30% share of the onshore market by 2026, due to their reliability and reduced maintenance needs.

🇰🇷 South korea awards 689 MW offshore

South Korea has awarded 689 MW of fixed-bottom offshore wind in its latest tender. A round dominated by publicly led projects, with none of the private sector proposals securing awards.

The auction included criteria for local content, national security, and industrial localisation. Some analysts point out that the Korean process is less transparent than in other markets and that political goals are outweighing competitiveness.

The four winning projects are as follows:

400 MW – Southwest Offshore Wind Power Demonstration Complex (KEPCO)

100 MW – Handong-Pyeongdae (Jeju Energy + Korea East-West Power)

99 MW – Dadaepo (Korea Southern Power + Corio)

80 MW – Aphae (CGO + KEPCO + Hyundai)

As can be seen, except for the 400 MW wind farm, the rest are small in size compared to the volumes currently being developed in the industry.

What stands out is that, except for the 400 MW project, all the winners will use Doosan Enerbility’s 10 MW offshore turbine, which will be installed for the first time at commercial scale.

A move that strengthens local industrialization, one of the core pillars of Korea’s energy policy. We have previously covered this turbine in Windletter. It is also important to remember that Siemens Gamesa and Doosan Enerbility signed an agreement to manufacture the SG15.0-236 DD nacelles.

A second auction is expected later this year, where greater competition and awards are anticipated.

🤝 Envision and GES sign agreement for wind turbine installation and O&M

Envision and GES have signed a strategic partnership to collaborate in the European wind sector. GES will be Envision’s main partner in Europe for the installation, commissioning, operation and maintenance of wind turbines.

Envision has been exploring the European market and establishing commercial contacts for some time. This alliance secures a local partner with experience and technical capacity, which may serve as a business card for potential clients.

The maintenance agreement also provides a level of certainty for developers. After-sales service is critical, and Chinese OEMs need to build local structures and partnerships to ensure long-term service for their turbines, covering contractual availability, spare parts and regulatory compliance.

This move could indicate that Envision is close to signing its first contracts in Spain or Europe, something that has been rumoured within the industry, although nothing has been made public so far.

🌬️ Siemens Gamesa receives first orders for the SG7.0-170

It can now be officially said that Siemens Gamesa is back on the onshore board. The company has confirmed the first orders for the SG 7.0-170 platform (the renamed SG5.X), which was withdrawn from the market in 2023 due to quality issues.

This milestone was announced by Vinod Philip, CEO of Siemens Gamesa, during Siemens Energy’s Capital Markets Day. Specifically, he stated that two agreements have been closed in Germany in recent days, with several more potentially to follow in the coming months.

This announcement adds to the first order for the SG5.0-145 (2.0), revealed last July: seven units destined for a wind farm in the Basque Country. Additionally, a single unit was recently sold for the expansion of a wind farm in Spain, as spotted by chance on LinkedIn.

No details have been disclosed about the wind farms or the volume of the orders. Given that they are in Germany, they are likely small orders, which would make sense as a way to “start turning the wheel.”

It is also confirmed that SGRE is abandoning its previous onshore turbine naming: the 4.X series is now called SG 5.0, and the 5.X series becomes SG 7.0. A rebranding effort aimed at distancing from the problems these platforms have faced.

Vinod Philip also mentioned that the medium-to-long-term strategy for onshore is to transform the division into a “focused, service-centric business,” although it is not entirely clear what that means.

🌪️ Paulo Soares steps down as managing director of Sany Europe

An interesting development in the European wind sector and the ongoing push by Chinese OEMs to enter the region: Paulo Soares is stepping down as Managing Director at Sany Europe after nearly two years in the role.

According to his farewell message, the decision appears to be personal: “I have decided to amicably end my working relationship with Sany Renewables in Europe.”

Paulo also shared: “I have tried to shift the narrative around the wind business in China. From the perceived ‘enemy’ to a necessary enabler. I truly believe this. We can only improve by competing with the best and leveraging everyone’s strengths.”

In recent times, Paulo has been one of the most prominent public voices advocating for the arrival of Chinese OEMs in Europe. From our perspective, he had become something of an “unofficial spokesperson” for these OEMs, some of which maintain a more public profile than others.

The news comes as a surprise, especially since Sany recently announced two contracts in Germany (2 turbines) and Spain (1 turbine).

Industry rumours suggest that Soares’ departure might signal a shift in Sany’s strategy in Europe, a market that has proven extremely complex for Chinese OEMs and where patience is key.

Indeed, Soares’ message also included this reflection: “In Europe, we compete against some of the best, and long-term success requires relentless and consistent determination.”

🔧 Repair of a Vestas V162 nose cone

Via the LinkedIn account of Dario Alejandro Taborda, a Vestas technician in Argentina, I came across this curious nose cone repair operation on a Vestas V162, filmed from a drone’s perspective.

It’s fascinating to see how, thanks to the technicians’ rope-handling skills, they’re able to set up a hoisting system to install the new cone. The lift is entirely manual, requiring the technicians to make several trips across the nacelle roof to gradually raise the cone.

This video highlights, on one hand, the ingenuity needed to design repair procedures for many components, and on the other, the importance of technicians’ rope access skills.

Honestly, it’s hard to imagine how a nose cone could break while a turbine is in operation. The most likely scenario is that it was damaged during installation.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace, RenerCycle and Nabrawind our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.